Public opinion polling can provide

information as to how different segments within the electorate view issues,

parties, or candidates. Every year, political parties in Canada both federally

and provincially spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on market research and

public opinion related services to help shape their communication strategies

and campaign platforms. When it comes to municipal politics, however, polling

can be a trickier matter.

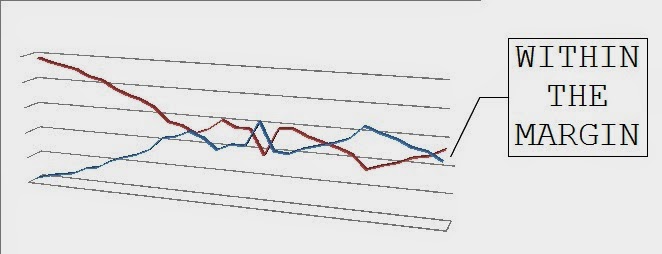

Poll after poll, Toronto's mayoral

candidates in 2014 jockeyed for the lead as media outlets intensified their

coverage and voters became more alive to the issues. But why is it that we hear

about people's attitudes and opinions towards mayoral candidates but not City

Council candidates? How hard could it be to ask residents of a certain area how

they view their City Councillor?

It’s actually a lot harder than one

would think, both in theory and practice.

One of the major problems with which

the polling industry is grappling today is low response rates. Today's public

has very little patience to participate in public opinion surveys and often

confuse pollsters with telemarketers. It’s quite difficult for pollsters to

find out what people are thinking when more and more of them are refusing to

share their opinions. Twenty or thirty years ago pollsters could acquire a

response from roughly six or even seven out of every ten households contacted.

This meant that polling could be done relatively quickly and cost-effectively.

Today some polls only receive responses from 2 out of every 100 households!

Almost every household had a land

line or home phone, meaning that a vast majority of the population (especially

voters) could be reached at home. Today, however, fewer and fewer households

have land lines, making people harder to contact. Mobile devices or cell phones

have begun (and will continue) to replace landlines as the most common means of

contact. Furthermore, many households are becoming cell phone only households,

especially among new Canadians and young Canadians ages 18-34. Pollsters today

must adjust their sampling frames to accommodate the widespread and

continuously growing use of mobile devices to avoid biases in their sampling.

However, blending or mixing land lines and cell phones is not a simple task.

The problems surrounding cell phone polling in a municipal context will become

more evident once we take a look at the sample situation below:

Assume for the moment that I have a

client who was running for Toronto City Council. My client has enough funds in

their war chest to conduct an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) poll with a

sample size of 500. With today's low response rates, it’s very plausible our

hypothetical poll would receive a response rate in the very low single digits.

Hypothetically, say I acquired a response rate of 3% (pretty reasonable for an

IVR poll!). This means that, in theory,

I would have dialed 16,666 phone numbers to get the 500 people needed to

complete the survey. However, just because someone is willing to take the

survey doesn't necessarily mean that they are eligible to vote. In this

situation, eligibility to vote is what we would call our incidence rate or the rate at which we are actually talking to the

people we need to be talking to. The incidence rate affects the logistics of

the poll (and client's invoice) because 16,666 numbers had to be called in

order to interview 500 eligible voters - not to mention the phone numbers

purchased from a vender but were unable to produce a response because they were

either out of service or belonged to a business.

Our problems aren't over yet. When

it comes to using landlines, it’s possible for a pollster to isolate a

geographic area by using the phone book. However, cell phones are not listed in

the phone book so in Toronto it is not possible to narrow down a cell phone

number to a specific section of the city before contacting it. A pollster can

conduct a city-wide municipal poll for a mayoral candidate by incorporating

cell phone numbers into their sampling frame with relatively little hassle

because it is possible to purchase lists of mobile numbers but all you know

about the number is that, if it’s a live number, it probably corresponds with

individuals residing within the City of Toronto (some people may have a Toronto

number but live outside of the city, but we can ignore this complication for

our example). Conducting a municipal poll for a City Council candidate is quite

difficult as we are not able to isolate cell-phone respondents who live within

a specific ward within the city. Leaving out cell phone respondents could bias

my sample and the results my client paid for would be skewed.

There are 44

wards in Toronto, so assuming that we wish to have 15% of our sample consist of

cell phones that means we need 75 cell phone respondents, and assuming our 3%

response rate, that means if we knew only the cell phones for our ward we would

need to contact 2500 individuals. But we have a second problem, roughly 1 out of

every 44 people that agrees to do our survey will live in the ward we want so

to get those 75 respondents we will actually need to contact 110,000 cell

phone numbers. And here’s one more caveat, cell phone number lists often also include

numbers that are not connected – that is they are assigned to be a cell phone

number, but no one has purchased that specific number yet, so we will need even

to call even more than 110,000 numbers! This would be both time consuming and quite expensive for my client.

For these reasons it is important

for municipal candidates to understand that they are uniquely situated within

the world of electoral politics and public opinion. They face a set of

challenges that their mayoral colleagues do not and they need to take these

obstacles into account if they are serious about conducting market research.

No comments:

Post a Comment